Jack Spector speaks in 1979!

WMCA

Good Guy fan John F. Porcaro contributed this article to the WMCA

Good Guys Web Site.

It was sent to him by New York Radio historian Vince Santarelli

(editor of the Apple Bites Radio Newsletter). It captures Jack Spector at

his best; funny, natural and full of enthusiasm.

The article originally appeared in the 3/14/79 - 3/21/79 issued

of "The Aquarian"

JACK SPECTOR ON THE HALCYON DAYS OF AM RADIO

The WMCA 'Good Guys':

Where Have They Gone ?

by Jeff Tamarkin and Andy Edelstein

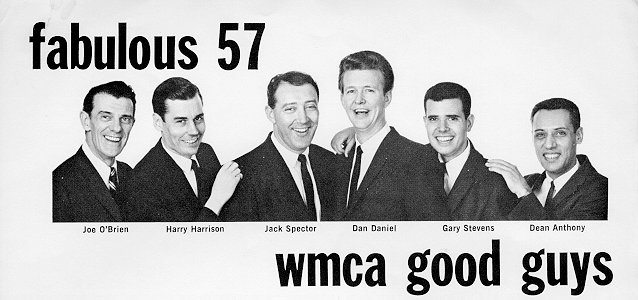

Disc jockeys singing promotions for themselves?. Disc jockeys with personalities? Good Guy sweatshirts and 'name it and claim it." "Look Out street, here I come!" The Wooleyburger, Benny, and the Off-Key Singing Club... WMCA! Fabulous 57/the home of the hits/the home of the Good Guys!

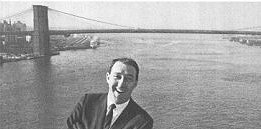

Jack Spector remembers it all: For the better part 1960s, Spector held the 1-4 slot on WMCA, participating in a manic, but creative, style of radio long since vanished from New York, if not the U.S. During this time, AM radio was king and three stations battled it out for New York's teenage ears-WABC(the "all-Americans", featuring Scott Muni and "Cousin Brucie" Morrow), WINS(whose saving grace was "Murray The K", renowned submarine-race watcher and self-proclaimed "Fifth Beatle"), and WMCA (with their lineup of six easily identified Good Guys). WMCA was the station that hooked the hipper kids--the ones caught in between the penny-loafer set and the Cuban-heeled cliques. WMCA had a larger playlist and was more innovative (playing more r&b and-obscure 45s) and the deejays were zanier than their competitors, making even the commercials for Tackle pimple cream and Great Shakes seem less offensive.

Today, the lines are blurred between the FM and AM bands, except for one feast of nostalgia which, for three years, has maintained if not the form, then certainly the spirit of WMCA-the Saturday Night Sock Hop, 8p.m. to 1 a.m. every Saturday on WCBS FM(101.1)- hosted by none other than "Big Jake" Spector, the brawny, Brooklyn-born Former Good Guy.

Listening to Spector jive with his listeners, take requests and hold contests,(he gives away CBS-FM T-shirts instead of Good Guys sweatshirts, oh well), play five hours of 50's and 60's singles, we're reminded how sorely the Good Guys and the concept of personality rock radio are missed. Could it be they were radio's last cultural heroes? After all, you don't see the faces of WPLJ's jocks plastered on city buses, do you? "

I love radio, but I hate what's happened to it," Spector said recently in his Brooklyn home. "Radio became a juke box, the idea being to play a lot of music and not say anything. The Good Guys had fun on the radio. We never took ourselves seriously. We said, "Let's get hokey, corny, do schtick, put ourselves on, put the audience on. We were the Beatles before the Beatles were the Beatles. We did dumb things and we were irreverent, and we couldn't sing. The Beatles came along and they could sing."

Spector, now in his late forties, had been plying his trade since 1955 in West Virginia, Albany and Chicago. When he arrived at WMCA in 1962, it was basically a schmaltzy, middle-of the-road station. On June 19 of that year, the concept of the Good Guys began--or rather, was stolen, from WABC, whose jocks, before they became all-Americans, briefly dubbed themselves "The Good Guys".

Spector says that Ruth Meyer, the WMCA program director, realized that ABC was using the concept wrong. So, "she said, 'Let's steal it.' She had a vision of a station that would play the hits, not just Sal Salvador and chicken rock." But Meyer's vision also allowed for the jocks to establish themselves as human beings, not just as faceless voices spinning records.

"A secret of the Good Guys," Spector reveals, was that we gave away something of ourselves on the air. It's one thing to be glib and clever, but people want to know a little bit about you." Indeed, each of the Good Guys had a schtick identified with him. Spector would close each show with a line given to him by R & B great Jackie Wilson .... Look out street, here I come" --which he still uses on CBS-FM. Gary Stevens invented a gurgling creature he called the Wooleyburger, and Joe O'Brien had his wisecracking, chipmunk-sound-a-like, Benny. And of course, the whole crew had access to an arsenal of ridiculous sound effects that they exploited at every opportunity.

The station built its following with gimmicks such as the Good-Guys sweatshirt (which now sells for $75 at collectors' flea markets), Good Guys record hops, and contests like the secret WMCA picnic. Their smiling faces peered from billboards on city buses. They were visible and personable qualities, which, Spector says, set them apart from the competition.

WABC never got involved with their audience like we did."They did nothing outside of the station. We made personal appearances we emceed the Beatles at Carnegie Hall, Forest Hills and Shea Stadium." The Good Guys, Spector said, tried to reach the average kid with discerning taste, and they spoke the language of their listeners--not the pseudo-cool patois developed by the popular Murray "The K" Kaufman. "Murray appealed to the Fonzie of his day." Spector suggests. "Murray had the kids with the DA haircuts and black leather jackets. We appealed to the Richie Cunninghams."

Another reason for the station's success, Spector maintains was its feeling for New York. While other stations imported their jocks from other markets, most of the Good Guys were native New Yorkers. "We had a feel for New York, and there was a better ethnicity to what we had." he says. "Joe O'Brien was an Irish kid, I'm a Jewish kid from Brooklyn, Harry Harrison was a Catholic, Dan Daniel was from Texas, and both Gary Stevens and B. Mitchell Reed were Jewish. The mix was beautiful."

The advent of progressive-FM radio in the late '60s, concentrating on longer songs recorded by new, album-oriented artists not previously heard on AM, spelled the end of the Good Guys era. With the new music came a new style of rock broadcaster: Deejays became air personalities speaking in Kahlil Gibran influenced circumlocutions. The Good Guys style of borsht-belt humor and streetwise savvy, wrapped around three- minute singles, now seemed quaint and outmoded.

The impact of WOR-FM and then WNEW-FM, New York's first progressive stations, became apparent on WMCA by the summer of 68. The Good Guys image was quietly dropped. Harrison defected to arch rival WABC. And there was no strong evening man (top-rated soul DJ Frankie Crocker was even tried for a while). MCA tried to enhance its playlist with a few album cuts, and cut down on the snappy patter, but it had become a station whose time was clearly over. The station never possessed the wattage of WABC, and realizing that the AM band couldn't support two Top-40 rockers. WMCA conceded to WABC and changed its format to all-talk in September, 1970.

Since then, most of the Good Guys have stayed in radio. Harrison is still at WABC; O'Brien is at WHUD in Westchester; Reed has become as popular on progressive KMET-FM in Los Angeles as he was as the night man on WMCA; Gary Stevens, who replaced BMR during the latter Good Guys era, is a vice president of a Minneapolis-based broadcasting chain; Don Davis, the original all-night jock, now calls himself Don Baldwin on all-news WINS; Dean Anthony is on WTFM, the beautiful music station; Dandy Dan Daniel was last heard doing voiceovers on Korvettes commercials. Spector stayed with WMCA, doing a sports show, when the one-two punch of progressive FM and tightfisted AM program directors KO'd the Top-40 format. He drifted to WHN, playing country music he couldn't stand, and then to pre-disco, mellow WKTU for a while-"which bored the *&#! out of me". Then was lured to CBS in 1975 on the premise that he was a link to the old era and would be a natural for an all-oldies station.

"I got a call from the program director, and he told me I was the guts of the Good Guys, the New York kid, and he needed me there. He said, "I want you to play those records that you introduced 12, 15 years ago." Spector was thrilled to oblige, as long as he could play the music he liked, and speak to his listeners in his naturally enthusiastic manner. "If I can't be me," he said, "I don't want to be in radio". Still, the Saturday Night Sock Hop, on which he encourages listener participation via request lines and contests, a la WMCA, is only a sideline for Spector, whose main business now is manufacturing eyeglasses and lenses.

"Radio is atrocious and that's why I've taken myself out of it," he remarks. "I won't even work at CBS full time. It's a terrible industry now. It's run by slide rule, and there's no personality left in it."

So, if Spector were to start his own radio station, what would it be like? Would it resurrect the concept of which he was an integral part -- that of the WMCA Good Guys?

"You beat me to it," he laughs. "That would be it." Although he agrees that the Good Guys ideal probably couldn't work today, he would incorporate some of those long dormant concepts into his station's format. "The ideal radio station has to appeal primarily to the young," he notes, "but don't forget that there are older people out there. There were people who listened to WMCA who hated the music, but loved the Good Guys."

WMCA Good Guys Home Page

WMCA Good Guys Home Page