Musicradio WABC Bill Epperhart Page

Bill Epperhart wrote the following description of what it was like to be an engineer at the greatest Top 40 radio station of all time. This is MUST reading if you are interested in Musicradio WABC. Bill talks about the set up of the studio, the fun of working with the different air personalities and the wonder of just being there. If you ever worked in broadcasting or ever even considered working in radio, Bill captures the feeling of "being there". And, you will also develop a true admiration for the talent and ability of the engineers at WABC. We all grew to know the Disc Jockeys and think of them as friends. But the engineers, like Bill, were just as much responsible for that on air magic.

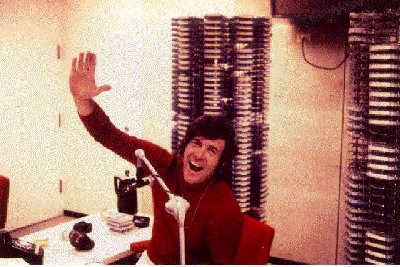

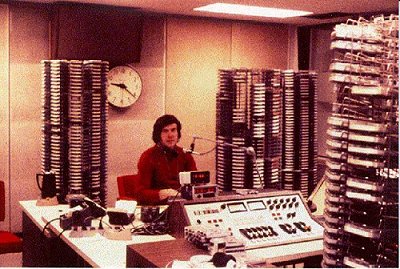

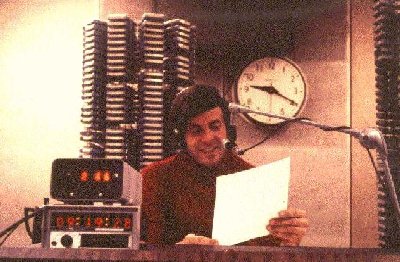

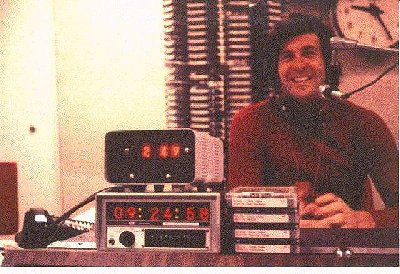

Bill also forwarded some pictures of the WABC studio in 1972 and there are some really fun airchecks from WABC including Dan Ingram playing a recording of Howard Cosell singing!

I was a WABC engineer during the early ‘70's. This was the era of Harry Harrison, Ron Lundy, Dan Ingram (was there ever a time when Dan wasn't there?), Bruce Morrow, Chuck Leonard and Jay Reynolds. Frank Kingston Smith started in 1971 and, as I recall, Johnny Donovan came on board in 1972.

WABC defied the conventional radio wisdom of the time. Most radio stations were either "combo", where the announcer operated the equipment, or had engineers who were quarantined in a separate room behind glass windows. WABC combined the concepts by having the disc jockeys and engineers work in the same room. This added to the on air spontaneity for which WABC was so famous. Ingram could do a 180-degree change of direction in a split second and the engineer would stay right with him. By using the best features of both approaches, the disc jockey could be much more versatile.

The presence of an engineer also added an additional element that the disc jockey could use. Dan got Jerry Zeller to sing "I Left My Heart in San Francisco" on the air and, in one of his openings, offered Jerry a hundred bucks to shave his head.

Most radio stations had very complex "on air" control rooms that could do everything, just in case the format changed without notice. WABC had a full complement of high tech "production" rooms, but the "air studio" (8A) was designed specifically to play Top 40 music on the radio.

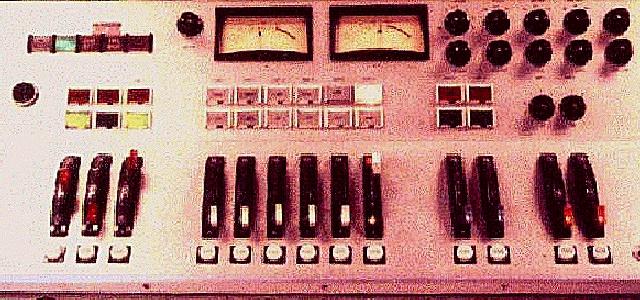

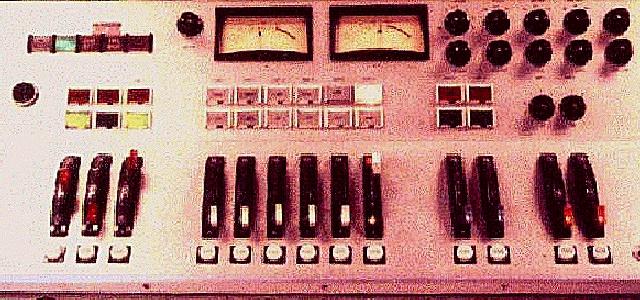

The console had only 13 faders (volume controls). The start buttons were above the faders and the dials in the upper right were for monitoring (headphone and speaker levels, etc.). We didn't use turntables and "the blue wall" (there's a trivia question for you) wouldn't let us install compact discs because they didn't want us using anything that hadn't been invented yet.

"Working The Board At 77 WABC"

Maybe you have worked in college or commercial radio and know what it is like to do a "Board Shift." If you REALLY want to know how the WABC console worked, this might be of interest.

The WABC console in Studio 8A was custom designed for "Top Forty Radio." Built for speed, it did little else. The faders (volume controls) were grouped by function; Microphones, Tape Cartridges, Reel-to-Reel Tape Machines, Remote Feeds.

If you wanted to hear something without putting it on the air you pulled the fader all the way down and pressed the white "CUE" button just underneath it.

Fader 1 was the Disk Jockey's Mic. The red button turned it on and muted the disk jockey's speaker to prevent feedback. The green button turned it off.

Fader 2 was a second studio mic that we didn't use. The engineers removed the light bulb in the Off button and kept the fader closed so we wouldn't "go for it." If we needed a second mic or Channel 1 went bad, we had a backup.

Fader 3 was the Newsman's Mic. The news booth was a room to the Disk Jockey's right and the engineer and newsman could see each other through a strategically placed mirror in 8A.

Faders 4 through 9 controlled the Tape Cartridge Machines (four to the engineer's left, two to his right). The top button started the cart and reset the digital count up clock to zero. The bottom button cut the audio, but did not stop the cartridge. Tape cartridges were actual loops that "recued" when they sensed a control tone at the beginning of the audio. Stopping a cart and putting it away "uncued" is a cardinal sin in radio. If we had a good reason for stopping a cart, we did it using the Stop button on the cartridge machine itself.

Faders 10 and 11 were associated with the two Reel-to-Reel Tape Machines in Studio 8N. The "News Control" Engineer was responsible for recording any "network feeds" and cuing them up for the board engineer who could start and stop the machines from 8A.

The last two faders were for remote audio feeds. Sound that originated from someplace else. An old radio term for a remote feed is "nemo" or no name. It could be a ball game, election returns, another studio on the floor or anything else. Remember Jules Verne's mysterious Captain Nemo? Above each remote fader was a ten position switch to select various audio feeds that were set up by the 8N Engineer. Position 1 was always the ABC Radio Network, position 10 was a 1 kilohertz tone for calibration purposes and the other eight varied. Every control room on the floor could tap into these ten channels.

The upper left side of the console contained a "Sonalert" that was supposed to sound if the transmitter went off the air. Indicator lights showed the status of things like echo on/off and emergency power.

The dial to the left of the meters was the Master Level Control for the entire console.

The left meter monitored the board output and the right meter could be switched to monitor the board (in case the left meter failed) or the air signal (off a receiver in the transmission room) or WPLJ-FM.

The dials to the right of the meters were for monitoring and were set at the beginning of a shift. There were four, three position switches (Air, 8A, FM) for the right meter, 8A speakers, disk jockey headphones and engineer headphones. There were also individual volume controls for the disk jockey's speaker and headphones, engineer's speaker and headphones, news booth speaker and cue speaker.

Although you could set up the board in many ways, typically we had the room speakers monitor the console and our headphones monitor the air receiver. By setting the right meter to monitor air, we also had a visual indication that the transmitter was broadcasting audio when we took the headphones off.

Once you had the console set the way you wanted it, the focus was on the microphones and the cartridges. Looks pretty simple doesn't it? Think anybody could make it sound good? Think anybody could make it sound great? Many tried. Some succeeded and others failed. I saw one new engineer turn a very talented, highly confident, veteran disk jockey into a mass of quivering jelly within less than fifteen minutes. A pitiful site.

To a WABC Broadcast Engineer, this console was a racing machine. We could give the disc jockeys anything they wanted. Of course, it was one thing to segue a few records and quite another to be sitting there during drive time. The best built car in the world won't save you at 150 mph if you are not a very good driver, and the air checks demonstrate how complex the "on air production" could get.

WABC was one of the first radio stations to have a two-sided digital count up clock that reset to zero when we started a new commercial, jingle or record. It was designed and built by Eric Rosenthal, another WABC Engineer, and used for many things besides "talk ups" and keeping track of where we were in a record or commercial. Yet another tool in our arsenal, it allowed us to easily "pre-roll" a record or jingle intro under a commercial so the vocal started just as the "spot" (commercial) ended. Of course it helped that we had everything from record intros to commercial lengths timed to a quarter of a second!

If you look closely, you will see a light bulb next to the clock on top of the console. This was hooked up to four timers that corresponded to the top four songs and lit when any hit zero. When I was there, we played the top four songs every 70, 80, 90 and 100 minutes respectively. These intervals weren't carved in stone but varied over time because the programming at WABC was dynamic. The rest of the music was taken from the Musicradio Survey and about a thousand additional records corresponding to various categories of oldies.

While WABC had a tightly controlled program format, there was tremendous latitude when it came to the music selections. Few stations gave air talent the kind of control exercised by the disc jockeys at WABC. A close study of the Musicradio Survey shows only 25 records. The times these songs were played, and the records chosen from the additional categories, were determined by the disc jockey and written on the Musicradio Survey. Many factors were used to decide what song came up next. These included the spot load, whether we were back timing into a network newscast and the audience demographics of that "day part." The common thread that ran through the WABC programming was the Musicradio Survey. The other categories determined the differences between Harry Harrison's morning choices and Cousin Brucie's teenage oriented play list.

By the way, just as most of the engineers didn't like to be called "board ops," many on the air staff didn't like the moniker "Disc Jockey." The Musicradio Survey reveals that the "politically correct" title was "Air Personality."

Obviously there was a lot of science going on here, but what did it all mean? Well, as Ron Lundy once said; "It don't mean nothin'." These guys could make any radio station sound good. They all had an incredible knowledge of timing, humor, music and on air execution. They knew all the rules in the book, which was why they were so good at bending, breaking or just throwing them away. The engineering design enabled them to do what they wanted with much less effort than was required anywhere else.

Studio 8A was active twenty-four hours a day. Engineers rotated through every two hours. The only time everything stopped was late Sunday night/Monday morning when the station went off the air for transmitter maintenance. It was then, when all was quiet, that you realized just how neutral the room really was. The walls were beige, the carpet was gray, the acoustical tile was white and there was no magic at all. The magic was in the people.

When Harry Harrison arrived Monday morning, the room came alive. It reflected his personality and was a magic place to be. As Ron Lundy sat behind the microphone at 10 a.m., everything changed. The magic was still there but it was a different kind of magic, it was Ron's magic. Ron owned that room and everything in it until 2 p.m. when he handed it off to Dan Ingram. More magic.

One of the great things about working at WABC was that when you sat opposite these guys, you became part of the magic too. Six million people a week were at the ends of your fingers. If your name was mentioned, the whole world heard it, or at least a few hundred thousand of your closest friends. For a 22-year-old right out of college, life didn't get much better.

Different people used the tools in different ways. Dan exercised complete control over every aspect of the sound. He would call for the microphone with a roll of his fingers, make a notation in the log, talk while throwing cues with the pen still in his right hand, then signal for the mic to be cut with his left. Every gesture was smooth. There was no wasted motion. He was like a conductor, controlling a symphony orchestra. When you worked with Dan, you just got into the flow.

Bruce Morrow took a different approach. Like Dan, he was always there, always in control, but Bruce preferred to have the engineer "fly the plane." If you were good, and gave him the sound he wanted, Bruce let you do it. I spent many happy hours working with Cousin Brucie and learned to "read" him well. He was a consummate professional, so consistent in his approach that we never discussed what we were doing. We just did it. He also became a very good friend.

There are many stories concerning what was done on the air at WABC, and some really off

the mark explanations describing how these things were accomplished. Those of us that

worked there were probably guilty for many misconceptions because we were so vague when

asked questions about WABC's secrets. One theory held that we did the "Instant

Replays" with very fast tape cartridge machines that recued while the two second

"Instant Replay" jingle played. In reality, we always had two copies of the

Musicradio Survey records available because Rick

Sklar was a great believer in backup systems. We didn't do "Instant Replays" on

oldies.

Within a couple of years, the world moved on and I left WABC to, as Dan put it, "go on to bigger and better things." In 1975, Bruce and I were reunited at WNBC until he left in 1977. After fifteen years of New York radio, four more as a Television Project Manager at NBC and finally, as an Engineering Administrator at the ‘92 Olympics in Barcelona, I left the business. Today I manage computer systems for a Health Care Corporation.

I haven't been in contact with anyone from WABC for many years, but still catch Harry, Ron, Dan and Bruce on WCBS-FM from time to time. There is something comforting knowing they are still there. Sort of like an anchor in your life. They say you can't go home again, but WCBS-FM comes close.

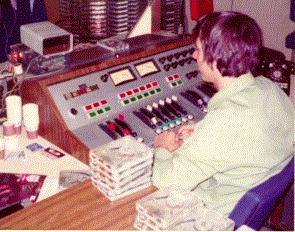

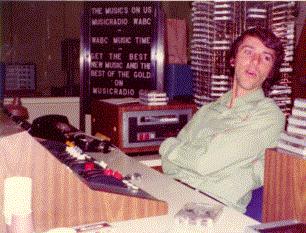

I've attached some photos I took in 1972 when Bob Ryan (pictured) and I were working with Bruce Morrow. Bob eventually left the business and went on to become a state senator in Nevada. This is what the room in the virtual tour looked like before it was refurbished. The engineering philosophies behind both designs were essentially the same.

Memories of Working With Cousin Brucie

At one time or another every WABC Engineer worked with every WABC Disk Jockey. Depending on who was sick or on vacation, an engineer's schedule could change dramatically. Over time however, patterns emerged. Few had 9 to 5 schedules and the engineering demographic ran from 20 year olds to people in their 60's. One engineer, Harry Lang, had started with the company the year after I was born.

Some engineers never saw the light of day. Others would arrive at 5 am and be on the golf course by 2 in the afternoon. Those that had been there a few years and had some seniority, tended to work with Harry and Ron. The schedule fit their life styles. As a young member of the staff, I ended up doing the 4 pm to midnight tours, as did many of us in our twenties. This fit our life styles.

Dan's show ended at 5:54:30 pm, followed by the network news and the 6 O'clock Report, with Bob Hardt. By the time Bruce slipped in behind the mic at 6:15, the office staff had left, the pace in the newsroom slowed, and the games were about to begin.

The first order of business came from Bruce. "Turn up the speakers, let's get a little excitement in here." From there we would set up the show, record the one minute network newscast that would play back at the end of the hour and settle in for whatever might happen next. At 7 pm, Cousin Brucie would call "Cousin Irving" at the Stage Deli and dinner would be on it's way.

Cousin Bruce Morrow was fun. A truly happy person, who didn't take himself too seriously, he was quick to laugh and had a great rapport with the staff. Insults and one liners flew back and forth across the console faster than the music carts.

"Bruce, are you sure you want to segue that cola spot into the one for acne medication?"

"That's right Billy. First we give ‘em the pimples, and then we take ‘em away!!"

This line was delivered when we had visitors:

"Always remember Billy, I'm the boss and your nothin'."

One night I decided not to answer with the ritual "That's right Bruce, your the boss of nothin" and said "Gee Bruce, I'm really sorry you feel that way. All this time I thought you were a nice guy."

"Come on Billy, say it!"

"Say what Bruce?"

The humor was sophomoric, but it was fun and we always put on two shows; one on the air and another for the studio visitors. And speaking of visitors, you never quite knew who might be coming up. One night it might be the mayor, another night it could be a couple of Penthouse Pets.

Penthouse Pets?

Newswriter Tom Romano grabbed a cassette recorder and came flying in to interview them.

"Hey Tom, you didn't put any tape in the machine!!"

Tom knew it, and so did the girls, but it was a great interview.

Apart from the nightly rituals, I got to know Bruce away from the studio environment. He called one day to tell me that he had been asked to M.C. the Miss. Teenage New Jersey contest on the boardwalk in Seaside Heights. Would I like to come along? We would meet at the 30th Street West Side Heliport at 11:30 am, fly to New Jersey, and get back in time to be on the air at 6:15 pm. No problem.

I put my car in the ABC garage and hailed a taxi. As the cabbie headed east I said "It's the West Side." "No, the heliport is on the East Side." East, West, there couldn't be two heliports could there? On the other hand, Bruce always got his details right.

I made the cabbie wait while I confirmed that yes, I was at the right heliport and they did have a flight scheduled for Cousin Brucie, but it had been changed to 12 noon and "please have a seat and we will call you when we're ready."

11:30 - No Bruce. 12 Noon - No Bruce. 12:15 - No Bruce but "Okay, let's go."

Lets go? Do they know I'm not him? Should I remind them I'm not him? Will I miss my chance to ride in a helicopter over Manhattan? Maybe I'll tell them after we take off. What should I do??? I know, vocal exercises ("Hi Everybodeeeeeee, Eeeeeeeeeee").

The pilot sauntered to the Bell Jet Ranger with that John Wayne kind of confidence all flyers seem to have. I didn't have a clue as to what was going on but he seemed to be in complete control. Something was up and it wasn't just us. We flew down the East River, turned west over lower Manhattan, then swung north over the Hudson. Now I was really confused.

Bruce said go west, I went east, Seaside Heights is south, we flew north. What next? I looked down and saw a flat roof painted with a sign that said "30th St. Heliport." Oh boy, there were two. The cabbie and the folks that arranged the flight had made the same mistake.

There was Bruce waiting for the helicopter to land. As he climbed into the back, I turned and said "So where have you been?" - "Billy, I'll kill you!"

"Whadda ya mean Bruce? I had to come and get you!"

Well, we made it to New Jersey. The pilot circled the beach before we landed to give us an overview and Bruce got to crown Miss. Teenage New Jersey.

On the way back, I witnessed one of the things that made Cousin Brucie so special. We were running late and had to get back to the helicopter. Kids were stopping us and we were getting bogged down in the crowd. One of the contestants stopped Bruce and asked for an autograph. Without a pen, he couldn't comply, but he looked directly into her green eyes and said very softly "You're very beautiful." It was like a scene in the movies where the crowd just fades out and the background audio gets very low. There were only two people in the scene, Bruce and the girl, and the look on her face was one I'll never forget. She had died and gone to heaven.

An instant later reality snapped back into focus and we ran for the chopper. Back to Studio 8A, Broadcast House, where our work day was about to "begin."

WABC - The Physical Layout at 1330 Avenue of the Americas and Howard Cosell:

77 WABC was located on the 8th floor. Studios FM-1 and FM-2 were used by WPLJ but their offices were on the 9th floor. The rest of the floor was used by WABC.

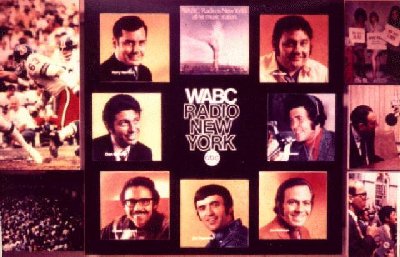

Stepping off the elevators into the WABC Lobby in early 1971, this is what greeted you. Counter clockwise are Harry Harrison, Dan Ingram, Chuck Leonard, Jay Reynolds, Jim Nettleton, Bruce Morrow and Ron Lundy. That's Bob Hardt in the lower right corner, just beneath Howard Cosell.

The studios/control rooms were located in the core of the building and the management offices lined the outside perimeter. Everything was painted an off white except for the north wall, which contained the offices of upper management, and was blue. For this reason, management was called "The Blue Wall" as in "Oh no, what's the Blue Wall up to now?" At some point, the place was repainted and the color of the north wall changed to yellow, but the name stuck.

8A was the WABC Air Studio. 8B was half the width of 8A but was designed as a backup in case the primary studio went down. It was also used for off air production.

8C contained a large studio room where the public service programming and station promos were recorded. On Sunday nights it was put on the air for the live call in shows that were part of the public service block.

8X was the Engineering Supervisor's Control Room where all the records and commercials were transferred to tape cartridge.

Finally there was 8N, News Control. The entrance to 8N was through the newsroom but the control room looked into 8A through a glass window. Manned 24 hours a day, it was from here that all the news carts were edited, network newscasts were recorded and the 50 kilowatt transmitter in Lodi, NJ was remotely controlled. Network newscasts were recorded on reel-to-reel tape machines here, "cued up" by the 8N engineer, then remotely started and played back by the board engineer in 8A.

8C, 8X and 8N were capable of recording "feeds" from the network, the output of any studio and the "air" signal. If the engineers knew something was "up" we tended to "roll tape" for posterity. We also had two Metro-Tech 4 track slow speed loggers in the Transmission Room. Each machine recorded the air signals of both WABC, WPLJ, the WABC Contest Phone Line and a Time Code Track. An entire 24 hours was put on only one 10 inch reel of tape. At this speed, the quality wasn't very good, but was sufficient for legal purposes. These machines recorded many of the classic air checks that otherwise would have been lost forever.

WABC/WPLJ had a staff of approximately two dozen engineers at any given time. Some were specialists while others covered many bases. Engineers were expected to know transmitters, production, operations and maintenance. The engineers were as close to the on air product as the disc jockeys, newsmen and staff announcers. Because they had access to all the equipment, were responsible for all the recording, and were very good at editing voice and music, it was the engineers who provided much of the grist for Dan Ingram's mill. Howard Cosell is a case in point.

Howard was on the air over many of ABC's broadcast outlets. He appeared on Local Television, Network Television, the Radio Networks and 77 WABC. These facilities were spread all over Manhattan. Television came from West 66th Street. the radio network was on Broadway and WABC/WPLJ radio were on 54th and 6th Ave. In order for Howard to meet his many commitments, ABC installed a high quality audio link to his house. The audio link was only one way and the producer would communicate with Howard over a regular telephone. Sitting in front of a microphone in the comfort of his home, Howard recorded shows for the radio network. As part of the preparation, the engineers in New York would make whatever adjustments were necessary to the line as Howard provided an "audio level." The level could have been the text of Howard's show, or even something as mundane as "Testing, 1, 2, 3." Not so with Howard. Bored by the process, he would pass the time singing and chatting with the staff at the other end of the line. Back in the studios however, the tape was already "rolling." And where did these tapes end up?

That's right, with Dan.

Mr. "No Problems" Jerry Zeller

One of the many reasons WABC radio was such a fun place to work was because bright, talented people tend to be "characters." One of the philosophies followed was that any time you began to feel a little insecure, a little unsure, you just looked around at the people you worked with and realized how normal you were. One "character" on the engineering side was Jerry Zeller. Jerry had a reputation for being cheap, which he played for all it was worth. He also wore a green eye shade whenever he "worked the board" because he didn't like the glare from the fluorescent lights. Air talent cued Jerry and he cued them right back. He was "Mr. No Problems" because nothing was impossible.

Attached are three excerpts from "The Jerry Zeller Series." The first is an Ingram Show Opening with Jerry sitting across from him (Ron Lundy can be heard "losing it " in the background). The second is WABC Newsman Gus Engelman covering a fire when he runs into Jerry, who happened to be passing by (this was never on the air). The third features the time Dan conned Jerry into singing on the air.

When Bill left Musicradio WABC, Dan Ingram did the following closing to mark the occasion:

On a sad note, Bill Epperhart died of pancreatic cancer on March 22,

2000.

This web site lost a true friend.

You can read his Memorial Page by clicking:

![]() WABC Musicradio 77

Home Page

WABC Musicradio 77

Home Page